Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Ray Harryhausen

This falls under the category of inspiration. When I was a kid I watched a lot of movies. The movies I liked best were the ones that featured special effects by Ray Harryhausen.

In the days before computer generated special effects, everything had to be done by hand. Spaceships and fantastic cities had to be made, either as miniature models or full sized sets. Strange creatures were either realized by an actor wearing a costume, or the way Ray Harryhausen did it which was through stop-motion animation. Stop-motion animation is similar to the animation that you see in cartoons, such as "101 Dalmations" or "Cinderella," only instead of using a series of slightly different drawings filmed in sequence to create the illusion of movement, in stop-motion animation you are moving a solid three dimensional object.

Ray would create miniature set pieces which he made to match the full sized sets used by actors. He'd position these sets in front of a small movie screen on which a single frame of the already filmed scenes from the full size sets so that the two blended seamlessly together. Then, he would take a miniature creature, skeleton, or dinosaur and position it so that it appeared to be interacting with the live action actor projected on the screen. He'd then photograph this new combination using one frame of movie film. He'd then advance the film projected on the screen one more frame, carefully adjust the position and pose of the miniature creature very slightly and photograph that new pose with a single frame of movie film. After hours of work and twenty four of these actions had been repeated he'd have exactly one second of film. Of course for a feature length movie of about ninety minutes in length, Ray had to create many, many minutes of animation, each minute equalling sixty of those seconds of work, or 1440 single frames, or adjustments for each minute of film.

His work required a lot of patience, and he also had to keep in mind what the entire action of the creature would look like projected at normal speed in the finished movie, so that it appeared not only natural, but as a living, breathing creature with its own distinct personality when people later watched the movie. If he made a mistake, such as bumping the miniature, or knocking over the creature, he'd have to start all over.

For me, his movies were, and still are, complete magic. When I was a kid, there was very little written about how special effects in movies were made, and most of what was written was wildly inaccurate. It wouldn't be until "Star Wars (episode IV-A New Hope)" was released in 1977 that special effects secrets would suddenly get a lot of attention. As a kid, I understood that when I saw the Wolfman, or the Frankenstein monster I was really seeing an actor wearing incredible make-up, but Ray Harryhausen's creatures and dinosaurs were definitely not actors in costumes. They were something else entirely, but they seemed to be very real and very alive. I was even more impressed with them once I knew how they were created.

I did make some stop-motion animated films of my own beginning in junior high school, but never became a professional stop-motion animator. Even so, there are lessons I learned from the work of Ray Harryhausen that I've brought to my work in comics. The first thing I learned is that if you are going to tell stories using non-existent creatures in them, it's incredibly important to make them seem real. You need to convince the reader that these are living, breathing creatures with their own personalities and behaviors, that live in their own habitats and behave in a manner that suggests that they are interacting with their world in a believable way. Ray learned this from another stop-motion animator named Willis O'Brien who was responsible for the special effects in the original (and best) "King Kong" (1933). In "King Kong" there is a famous scene in which Kong fights an allosaurus. O'Brien could have just had the two creatures grapple with each other and still impressed people, but he went an extra step. Not only does Kong use wrestling and boxing moves to fight the dinosaur, but my favorite detail is the way the allosaurus swishes its tail back and forth when it's getting ready to pounce. O'Brien made his stop-motion puppets characters and actors, something Ray Harryhausen did as well. My favorite detail of Ray Harryhausen's is in "20 Million Miles to Earth" (1957). It's a scene where someone turns on a light and disturbs the baby alien Ymir, who blinks and starts rubbing his eyes at the brightness of the light. This detail makes the Ymir seem even more like a living creature reacting with its environment.

The second thing I learned from Ray Harryhausen is that your work and your play don't have to be two different things. As a writer, or any kind of artist, your workday never really ends. Even if you are not actively writing, or drawing, or playing music, you are thinking about it, generating ideas, and reading, watching and encountering things that might inspire your next big idea. I write about the things that I enjoy when I'm not working, and enjoy the sorts of things I write about when I am.

Today is Ray Harryhausen's 90th Birthday. If you've never seen one of his movies then watching one is a great way to celebrate. I recommend "The 7th Voyage of Sinbad" and "Jason and the Argonauts" most of all. While you're watching, pay special attention to the creatures in the movie and try to notice details about how Ray Harryhausen made them seem like they were alive and not just moving.

You can also see all of the different creatures that Ray Harryhausen has animated by going here. By clicking on the photos you can see brief bits of animation for each creature.

Here are some of Ray Harryhausen's other movies you might enjoy:

"Mysterious Island" (1961)

"First Men in the Moon" (1964)

"Mighty Joe Young" (1949)

"The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms" (1953)

"One Million Years B.C." (1966)

"Clash of the Titans" (1981)

"The Golden Voyage of Sinbad" (1974)

"Earth Vs the Flying Saucers" (1956)

Labels:

inspiration,

Ray Harryhausen,

stop-motion animation

Thursday, June 24, 2010

Working with Artists

Some of the questions I asked most frequently by kids (and often adults) involve working with artists as a writer. "Do you get to choose the artist who illustrates you story?" is one and "Do you and the artist work separately, or together?" is another.

The answer to both is "it depends."

Generally, the person I work with most closely is the editor. For most projects the editor will decide who will draw the story I've written. For example, some of the questions that might run through the editor's mind when choosing an artist are: How they choose the artist depends on a number of things. has the editor and artist worked well together on previous stories? Has the artist worked well with the writer on previous stories? has the artist drawn these particular characters before? Does their style fit the mood of the story? can they draw fast enough to meet the deadline for the story? Is this artist currently available to draw this story?

Most of the time, the editor will assign an artist to illustrate a story without even telling me who will be drawing it. This is how it is most often done on the various Cartoon Network titles I've worked on. For each of these titles, the editor will choose from a small group of artists who have demonstrated an outstanding ability to draw the characters and situations to reflect the look and feel of the television show that inspired them. If you look at the credits in several issues of SCOOBY-DOO, CARTOON NETWORK ACTION PACK, CARTOON NETWORK BLOCK PARTY, or any of the other titles, you'll see the same names appear over and over again. On these titles, we've all been working together for so long that we know that our combined efforts will come together in a fun story.

For other comic book projects I've written, the artist is usually assigned at the same time I am, and if I'm familiar with their work, I can write my script to showcase their strengths as an artist. For projects that I generate myself, I work with the editor in choosing an artist who is best suited for that particular project. In this case the editor and I will each come up with a list of artists we think would be good for the project and then decide on one we both like. If they are available, and like the project, they're hired. If we can't get them, we pick one of the other artists we liked.

One of the best part of writing comics is getting to work with so many different talented people, and seeing how they take my written scripts and translate them into illustrated stories. The finished result is always a surprise, even when you've worked with someone many times.

As to whether an artist and myself work together, or separately, it varies from project to project and from artist to artist. Most often, the artist and I will never meet, or even email each other until long after a project is finished. There are still so many people I've worked with, often for years, whom I've never met or even spoken too. We only know each other through our work together.

For some projects I will send the artist some reference material to help them. These can be photographs of locations featured in the story, or hand drawn maps I've made of how the characters should move through a location, or even sketches of new characters and creatures. All of this is done to make their job easier, and to help them get a better sense of what I imagined in my own mind when I wrote the story.

On a few occasions the artist and I worked very closely. We would talk on the phone several times a week. These conversations were often not about work at all, but simply us getting to know each other. This helped a lot. My scripts for these artists would get shorter over time, because so much of teh detail would get covered in conversation, and because I knew what movies or artists they liked, I could instruct them simply by comparing a scene in the script to a scene in a movie they'd seen, or a book they'd read, and say something like; "the house in this story should look something like the house in that movie," or "when the characters walk through these woods, the art should create the same feel as that part of that book where the characters were lost in a strange neighborhood." The artist will understand what I mean by this and it will help guide them when illustrating a scene in our project.

I've been really lucky. In all the years I've been writing comics, there have only been a couple of stories where I really didn't think the art fit the story well. Out of all the artists I've worked with, there have never been any whose work I haven't liked, and out of all of those that I've met, I'm friends with them all. I'm even friends with some I've only ever met through email.

I'm also happy to say that I've never had any real arguments with any artist I've worked with about how something should be done.

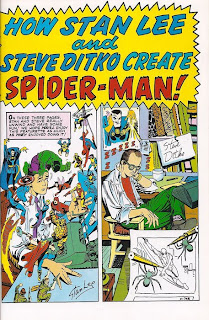

Below you can read a very tongue in cheek example of a comic book artist and writer working together. This was by writer, Stan Lee and artist, Steve Ditko about creating Spider-Man and comes from THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN ANNUAL #1 from 1964.

The answer to both is "it depends."

Generally, the person I work with most closely is the editor. For most projects the editor will decide who will draw the story I've written. For example, some of the questions that might run through the editor's mind when choosing an artist are: How they choose the artist depends on a number of things. has the editor and artist worked well together on previous stories? Has the artist worked well with the writer on previous stories? has the artist drawn these particular characters before? Does their style fit the mood of the story? can they draw fast enough to meet the deadline for the story? Is this artist currently available to draw this story?

Most of the time, the editor will assign an artist to illustrate a story without even telling me who will be drawing it. This is how it is most often done on the various Cartoon Network titles I've worked on. For each of these titles, the editor will choose from a small group of artists who have demonstrated an outstanding ability to draw the characters and situations to reflect the look and feel of the television show that inspired them. If you look at the credits in several issues of SCOOBY-DOO, CARTOON NETWORK ACTION PACK, CARTOON NETWORK BLOCK PARTY, or any of the other titles, you'll see the same names appear over and over again. On these titles, we've all been working together for so long that we know that our combined efforts will come together in a fun story.

For other comic book projects I've written, the artist is usually assigned at the same time I am, and if I'm familiar with their work, I can write my script to showcase their strengths as an artist. For projects that I generate myself, I work with the editor in choosing an artist who is best suited for that particular project. In this case the editor and I will each come up with a list of artists we think would be good for the project and then decide on one we both like. If they are available, and like the project, they're hired. If we can't get them, we pick one of the other artists we liked.

One of the best part of writing comics is getting to work with so many different talented people, and seeing how they take my written scripts and translate them into illustrated stories. The finished result is always a surprise, even when you've worked with someone many times.

As to whether an artist and myself work together, or separately, it varies from project to project and from artist to artist. Most often, the artist and I will never meet, or even email each other until long after a project is finished. There are still so many people I've worked with, often for years, whom I've never met or even spoken too. We only know each other through our work together.

For some projects I will send the artist some reference material to help them. These can be photographs of locations featured in the story, or hand drawn maps I've made of how the characters should move through a location, or even sketches of new characters and creatures. All of this is done to make their job easier, and to help them get a better sense of what I imagined in my own mind when I wrote the story.

On a few occasions the artist and I worked very closely. We would talk on the phone several times a week. These conversations were often not about work at all, but simply us getting to know each other. This helped a lot. My scripts for these artists would get shorter over time, because so much of teh detail would get covered in conversation, and because I knew what movies or artists they liked, I could instruct them simply by comparing a scene in the script to a scene in a movie they'd seen, or a book they'd read, and say something like; "the house in this story should look something like the house in that movie," or "when the characters walk through these woods, the art should create the same feel as that part of that book where the characters were lost in a strange neighborhood." The artist will understand what I mean by this and it will help guide them when illustrating a scene in our project.

I've been really lucky. In all the years I've been writing comics, there have only been a couple of stories where I really didn't think the art fit the story well. Out of all the artists I've worked with, there have never been any whose work I haven't liked, and out of all of those that I've met, I'm friends with them all. I'm even friends with some I've only ever met through email.

I'm also happy to say that I've never had any real arguments with any artist I've worked with about how something should be done.

Below you can read a very tongue in cheek example of a comic book artist and writer working together. This was by writer, Stan Lee and artist, Steve Ditko about creating Spider-Man and comes from THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN ANNUAL #1 from 1964.

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

Making a Comic Book -- Step by Step

If you ever wondered how a comic book story was made from start to finish, now is you chance to find out. Using a page from "The Dragon's Eye - Part 2: Russian into Danger" from SCOOBY-DOO #60 I will take you through the steps from start to finish. You can click on any image below to make it larger.

Step 1: Everything starts with a story, or at least the idea of a story. Every story begins with what's called a pitch. In the pitch, a story is broken down to its most basic elements in about three or four sentences. In the case of the story here, it was one chapter of a six part story, and was probably pitched as something like this:

The Dragon's Eye - part 2: As the mystery of the Dragon's Eye deepens, the Mystery Inc. gang travels to Russia where they encounter Baba Yaga, a witch from Russian folklore. Baba Yaga is after a jewel encrusted Faberge egg. Can they stop her?

As you can see this is very basic, but gives the editor enough information to decide whether they'd like to develop the story or not. Maybe they've already done a story about Baba Yaga, or one set in Russia and don't want another one. In this case the story was approved and then I got to move on to step 2.

Step 2: Now that the story is approved the writer (in this case me) writes a script for that story. The script tells the artist everything that he will need to draw for the comic book story. The script describes the locations where the action takes place, who the characters are and what they look like, what the characters are doing in each panel, what they are saying, and even how many panels are on a page. Scripts vary in length depending on the story. I have written scripts for a 22-page comic book story that were over 50 pages long, and scripts for a six page comic book story that were only 2 pages long. Below is a page of the script for "The Dragon's Eye - Part 2: Russian Into Danger"

Step 3: The script now goes back to the editor. The editor will read it and decide if anything needs to be changed by the writer. If everything is okay then the editor sends it on to the artist who is going to draw the story.

Step 4: The person who draws the story is called the penciller. In this case the penciller is the talented Joe Staton. The penciller reads the script and then decides how they are going to draw everything based on the writer's script. The penciller also thinks about the best way to make the action flow smoothly from panel to panel, and to keep the dialogue easy to follow between one character and another. Below are Joe Staton's pencils for this page. Compare his drawings to the descriptions in the script page above.

Step 5: In the old days, before computers, lettering was done directly on the page of art containing the pencils. After the lettering was done, the art would be passed on to the inker. Now both these steps are done more or less at the same time, but we'll start with the lettering for the sake of tradition. The lettering is the process in which all of the dialogue, including the balloons that contain them, the descriptive narrative captions, and the sound effects are added to the artwork. Oftentimes, to make things clearer for the letterer, the editor or writer will mark a copy of the script and the pencils like this:

and this:

If you look at the copy of the script page just above, you'll notice that numbers have been placed next to each line of dialogue. If you look at the copy of the pencils just above, you'll notice that rough balloons have been drawn over the art with numbers inside them. The numbers in the balloons go to the numbers on the script. This shows the letterer which lines of dialogue should go in which balloons, and where they go on each page so as to not block out important bits of artwork and so that the dialogue is easy to read across the page. It also makes it less likely for mistakes to be made where a character will be speaking the wrong dialogue.

Step 6: Now that the letterer (in this case Tom Orzechowski) has these marked versions of the script and pencils, he can use them as a guide to add the actual lettering to the story. This used to all be done by hand, so a letterer had to have excellent penmanship. Now it's mostly done on computers.

Step 7: It used to be that the inker wouldn't do their job until the letterer had done theirs, but that's no longer the case, since the lettering is no longer done directly onto the pencilled artwork. The inker is the person who goes over all of the pencils in ink so that the artwork reproduces better when it's being printed. Many people think that all an inker does is trace the pencils. This is not true at all. An inker adds areas of black, and varies the thickness of their line to help make certain parts of the artwork stand out, and to make other parts sort of fade into the background. They can add atmosphere and texture to the art as well. Below is the inked artwork by Horacio Ottolini over Joe Staton's pencils. Compare this with Joe's pencils back in Step 4.

Here is the inked page with Tom Orzechowski's lettering.

Step 8: The final step is adding the color. This work used to be done by hand using special dyes on copies of the inked and lettered artwork. Now most coloring is done on computers. The colorist can use their skills to create mood and to bring emphasis to a character or object in a panel. For example, in the page below, colored by Paul Becton, notice how in panel 4 only Scooby-Doo and the egg he's trying to catch are colored in detail. The other characters are all colored in one pale shade of purple. This is because even while the other characters are present, they aren't what's important in this panel, so they are colored to fade into the background while our attention is in Scooby-Doo.

There you have it, the entire process from beginning to end in creating a comic book story. In future posts I will go into even more detail for each of these steps and will even have various editors, writers and artists talk about their parts in bringing a comic book story to life.

Step 1: Everything starts with a story, or at least the idea of a story. Every story begins with what's called a pitch. In the pitch, a story is broken down to its most basic elements in about three or four sentences. In the case of the story here, it was one chapter of a six part story, and was probably pitched as something like this:

The Dragon's Eye - part 2: As the mystery of the Dragon's Eye deepens, the Mystery Inc. gang travels to Russia where they encounter Baba Yaga, a witch from Russian folklore. Baba Yaga is after a jewel encrusted Faberge egg. Can they stop her?

As you can see this is very basic, but gives the editor enough information to decide whether they'd like to develop the story or not. Maybe they've already done a story about Baba Yaga, or one set in Russia and don't want another one. In this case the story was approved and then I got to move on to step 2.

Step 2: Now that the story is approved the writer (in this case me) writes a script for that story. The script tells the artist everything that he will need to draw for the comic book story. The script describes the locations where the action takes place, who the characters are and what they look like, what the characters are doing in each panel, what they are saying, and even how many panels are on a page. Scripts vary in length depending on the story. I have written scripts for a 22-page comic book story that were over 50 pages long, and scripts for a six page comic book story that were only 2 pages long. Below is a page of the script for "The Dragon's Eye - Part 2: Russian Into Danger"

Step 3: The script now goes back to the editor. The editor will read it and decide if anything needs to be changed by the writer. If everything is okay then the editor sends it on to the artist who is going to draw the story.

Step 4: The person who draws the story is called the penciller. In this case the penciller is the talented Joe Staton. The penciller reads the script and then decides how they are going to draw everything based on the writer's script. The penciller also thinks about the best way to make the action flow smoothly from panel to panel, and to keep the dialogue easy to follow between one character and another. Below are Joe Staton's pencils for this page. Compare his drawings to the descriptions in the script page above.

Step 5: In the old days, before computers, lettering was done directly on the page of art containing the pencils. After the lettering was done, the art would be passed on to the inker. Now both these steps are done more or less at the same time, but we'll start with the lettering for the sake of tradition. The lettering is the process in which all of the dialogue, including the balloons that contain them, the descriptive narrative captions, and the sound effects are added to the artwork. Oftentimes, to make things clearer for the letterer, the editor or writer will mark a copy of the script and the pencils like this:

and this:

If you look at the copy of the script page just above, you'll notice that numbers have been placed next to each line of dialogue. If you look at the copy of the pencils just above, you'll notice that rough balloons have been drawn over the art with numbers inside them. The numbers in the balloons go to the numbers on the script. This shows the letterer which lines of dialogue should go in which balloons, and where they go on each page so as to not block out important bits of artwork and so that the dialogue is easy to read across the page. It also makes it less likely for mistakes to be made where a character will be speaking the wrong dialogue.

Step 6: Now that the letterer (in this case Tom Orzechowski) has these marked versions of the script and pencils, he can use them as a guide to add the actual lettering to the story. This used to all be done by hand, so a letterer had to have excellent penmanship. Now it's mostly done on computers.

Step 7: It used to be that the inker wouldn't do their job until the letterer had done theirs, but that's no longer the case, since the lettering is no longer done directly onto the pencilled artwork. The inker is the person who goes over all of the pencils in ink so that the artwork reproduces better when it's being printed. Many people think that all an inker does is trace the pencils. This is not true at all. An inker adds areas of black, and varies the thickness of their line to help make certain parts of the artwork stand out, and to make other parts sort of fade into the background. They can add atmosphere and texture to the art as well. Below is the inked artwork by Horacio Ottolini over Joe Staton's pencils. Compare this with Joe's pencils back in Step 4.

Here is the inked page with Tom Orzechowski's lettering.

Step 8: The final step is adding the color. This work used to be done by hand using special dyes on copies of the inked and lettered artwork. Now most coloring is done on computers. The colorist can use their skills to create mood and to bring emphasis to a character or object in a panel. For example, in the page below, colored by Paul Becton, notice how in panel 4 only Scooby-Doo and the egg he's trying to catch are colored in detail. The other characters are all colored in one pale shade of purple. This is because even while the other characters are present, they aren't what's important in this panel, so they are colored to fade into the background while our attention is in Scooby-Doo.

There you have it, the entire process from beginning to end in creating a comic book story. In future posts I will go into even more detail for each of these steps and will even have various editors, writers and artists talk about their parts in bringing a comic book story to life.

On Sale Today

Head to a comic book store near you for SCOOBY-DOO #157 which features 2 installments of my popular "Velma's Monsters of the World" series. This issue Velma spotlights Yama-Uba and the Griffin. Both stories were drawn by Fabio Laguna with Travis Lanham providing the lettering, Heroic Age the colors, and Harvey Richards editing. The creepy cover is by Vincent Deporter.

Friday, June 11, 2010

Putting the Words in the Bubbles

The response I hear the most when people find out that I write comic books for a living is "Oh, you put the words in the bubbles."

The person who actually, physically writes all of the words into the bubbles (actually called word balloons) is the letterer. This job used to be done completely by hand, but is now more often done using a computer. I don't do this job, and I don't think this is what people mean when they respond about me putting the words in the bubbles.

Instead I think their assumption is that I just write the dialogue which appears in the balloons, and that the artist comes up with all of the visuals all on their own and somehow the two elements come together to form a complete story.

The truth of the matter (and this in no way is meant to suggest that the artists don't make valuable contributions of their own) is that I also have to describe everything that goes on in each panel on ever page of a comic book story, usually including how many panels are on each page, so that the artist knows what to draw. That means I have to describe the locations where the story takes place, whether it is night or day, raining, snowing, or hot and sunny, what the characters look like, what they are doing, what their expressions are like, if they are holding anything I need to describe what those things are and how important they'll be for the rest of the story and so on.

Since this is the part of creating comics that I know the most about, most of my posts here will concern different aspects of writing comic book stories. For right now, compare the panel above, (which was taken from "Man of a Thousand Monsters" written by me pencilled by Robert Pope, inked by Scott McRae, lettered by Swands, colored by Heroic Age, and edited by Harvey Richards) with the except from the script for the very same panel shown below. You can make the images larger by clicking on them.

Next week I will walk you through the entire process of how a comic book story is created from beginning to end.

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Behind the Scenes of "The Missing Mummy Mystery"

"The Missing Mummy Mystery" appears in SCOOBY-DOO #156 which can probably still be found at your favorite place to buy comics. I wrote this story. Scott Neely drew the art. Heroic Age colored it, and Travis Lanham provided the lettering. Harvey Richards was the editor.

A couple of posts back, I mentioned my fondness for old monster movies and how I liked reference them in various Scooby-Doo stories. "The Missing Mummy Mystery" is no exception. As you might have guessed, for this story, my inspiration came from "The Mummy" (1932).

This movie features Boris Karloff as a living mummy who believes that the woman he loved thousands of years ago has been reincarnated as a modern day woman. The most famous scene from the movie comes near the beginning when an archeologist played by Bramwell Fletcher translates an ancient scroll which brings the mummy to life. The mummy shuffles over to him, takes the scroll, and shuffles away leaving the poor archeologist cackling with insanity. When his fellow archeologists ask him what's wrong he points to the empty sarcophagus and declares "He went for a little walk" before cackling with madness once more.

That very scene (shown above) was what inspired the entire story of "The Missing Mummy Mystery" and the idea of a valuable mummy seemingly vanishing from a museum collection by simply walking out the door under his own power. I also included a similar scene in which the night security guard, David Manners, stumbles across the walking mummy.

I also named several characters after characters and actors from "The Mummy." First was David Manners, the night security guard. In the movie, David Manners played Frank Wemple, son of Sir Joseph Wemple. David Manners was also in the movie "Dracula" (1931). Here's David Manners in "The Mummy."

Below you can see David Manners as the night security guard, along with Sir Wemple the museum director as they appeared in the comic book.

I named the daytime security guard, Steve Banning, after a character from "The Mummy's Hand" (1940) which also featured a living mummy on the loose. Steve Banning was an adventurous archeologist played by Dick Foran. Here's what he looked like in the movie. (He's the one NOT wrapped in bandages).

Here he is as he appears in "The Missing Mummy Mystery."

Now you know the story behind the story "The Missing Mummy Mystery."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)